by Dr. Nancy Power, Ph.D. in Entomology | Thursday, Jan. 13, 2022 –

Visiting my family in Pennsylvania in October 2019, I found my sister Rita in a pitched battle with thousands of spotted lanternfly (SLF) adults and egg masses in the yard of her suburban Philadelphia home. I helped her scrape egg masses off the bark of her ornamental trees. Earlier in the season, she had used a vacuum and extension-prescribed, homemade circle traps to stem the onslaught of adults and nymphs (immatures). As fast as she killed them, though, more flew in from the neighboring yards.

Despite its name, the SLF is not a fly but a planthopper. Read on to learn more about its lifecycle, its favorite host plants, and what you can do to keep this invasive species out of North Carolina.

LIFECYCLE

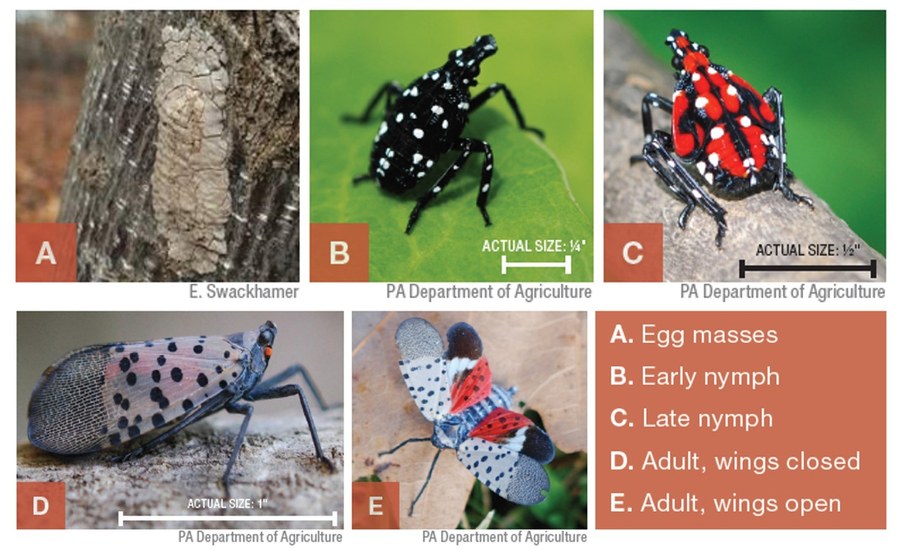

The SLF egg masses look like gray, smooth, slightly-shiny slime and can be found on any surface. The egg mass cracks and dulls as winter progresses. Eggs usually start hatching in May but can begin as early as March. Hatching is not synchronous.

The first through third stage nymphs are black with white spots, but the fourth and final instar is black, white, and bright red.

Update: SLF has been found in Forsyth County in North Carolina as of Jun. 29, 2022.

By September or October, all the surviving nymphs have become adults. The adults swarm and mate, and then the females lay eggs. adults die as temperatures dip below freezing, leaving only the eggs to overwinter.

Since the eggs last a long time and are inconspicuous, the egg stage is the most likely for the planthoppers to be transported to a new area by human vehicles. Gravid (pregnant) adult females are the second most likely to expand the species’ range.

All life stages of the spotted lanternfly, from egg to adult. See the full lifecycle in this PDF by Penn State Extension. Credit: Penn State Extension (Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture and Emelie Swackhamer).

ORIGINS & WHERE SLF HAVE BEEN FOUND

Originally from China, where natural enemies and natural plant defenses keep it under control, the SLF appeared in Korea in 2004 and then in Japan.

It first arrived in the U.S. in 2014 in Pennsylvania. Since then, it went from spreading at the rate of one new state per year to 10 states east of the Mississippi (Indiana, Ohio, New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, and West Virginia). The northern Virginia infestation spread from one square mile to 17 square miles within one year.

Unfortunately for North Carolina, a separate breeding colony was recently discovered in Carroll County in southwest Virginia, only 20 miles from the North Carolina border.

A few SLF sightings have occurred in North Carolina already. One adult was found dead on a Christmas tree brought in from another state. Five adults were detected on a WWII-era plane that broke down in Pennsylvania and returned to North Carolina in the spring. Fortunately, the bugs were sealed inside the plane and killed by the spring heat. All sightings in 2020 were of dead adult insects. The first specimen found alive in North Carolina was one adult in the Outer Banks. So far, though, no SLF populations have established in North Carolina that we know of.

Above: Early nymph stage. Credit: Lawrence Barringer, Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture. Below: Late nymph stage. Credit: Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture

DETECTION & CONTROL

The North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (NCDA) Plant Industry Division is bracing for the SLF arrival. The goal is to spot it quickly and eradicate it before it establishes a breeding population.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Plant Protection Act 7721 provides funding for North Carolina to complete a statewide survey for SLF and its preferred host, the tree of heaven.

Visual surveys and SLF circle traps will be implemented in:

- state parks

- rest areas

- rail yards

- hardscape businesses

- metropolitan areas

- tourist hotspots such as NASCAR, campgrounds, and beaches

Fortunately, the insect is relatively large, colorful, and unique-looking, making it easy to spot.

The NCDA has informational swag available to spread the word, including posters, banners, webcam covers, pens, coasters, and adhesive notes. You can request swag by calling Amy Michael, the NCDA cooperative agricultural pest survey coordinator, at 919-707-3749. Your county NC Cooperative Extension office may also have posters.

Besides asking citizens to help scout for SLF, the USDA has trained two canine helpers, one each for the western and eastern halves of the state. The dogs spent four weeks at the Georgia center where all USDA detector dogs are trained, followed by several weeks of practice in an SLF-infested area in Virginia. They run along until they detect the odor of an SLF egg mass, at which time they sit and receive a reward. As judged by lots of tail wagging, the dogs think the searching is a fun game.

Above: SLF egg mass partial cover. Below: Spotted lanternfly egg sac. Credit: Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org

CONCERNS ABOUT SLF IN NORTH CAROLINA

SLF is an example of an invasive species. These are species that make it to a new region, usually by means of people or vehicles and cause economic and/or environmental harm. They can drive native plants and animals to extinction, lessen biodiversity, and permanently alter habitats. Many invasives become nuisance pests or harm agricultural crops; the spotted lanternfly does both.

So far, the only crop on which economic harm is documented is European grapes (typical wine and table grapes), Vitis vinifera. The need for insecticides increases from about $50 to $150 per acre when SLF are present. Unfortunately, the mating swarms occur in the month prior to harvest, when insecticide options are more limited.

Adult spotted lanternfly feeding on grape (Vitis spp. L.). Credit: Lawrence Barringer, Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org

Because SLF is not in muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia) territory, it is unknown if the planthoppers will damage muscadines. Considering the SLF’s wide host range of more than 70 plant species, it will likely harm this other species in the same Vitis genus. SLF also causes issues in hops, especially sooty mold growth that renders the hops unmarketable. Some fruit trees are hosts as well.

SLF feed by sucking sugary juice out of the phloem tubes in plants. The juice contains a lot of sugar but not much in the way of amino acids, the building blocks of protein. Like other sucking insects, the SLF have to consume a lot of phloem liquid to get enough protein. Still full of sugar, the excess fluid is emitted onto the plant as “honeydew.” Black sooty mold grows on the honeydew. The mold looks ugly and blocks the sunlight needed by leaves to photosynthesize.

Above: Fungal mat at the base of a tree. This fungus is the result of sap flows and honeydew from the Spotted Lanternfly, Lycorma deilcatula. Below: Spotted lanternfly on a plum/cherry (Prunus spp. L.). Credit: Lawrence Barringer, Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org

In addition to harming ornamental trees, SLF’s sheer numbers make them a nuisance pest.

In New Jersey, at one point, so many people were calling the police about SLF that they impeded the 911 system. The police cannot address SLF! Instead, call Cooperative Extension or NCDA Plant Protection Division to find out how to manage SLF. You can start by scraping off the gray egg patches with a putty knife, credit card, or regular knife.

Penn State has directions for making a circle trap. The Plant Protection Division recommends circle traps rather than sticky bands around the tree trunk. The sticky bands get a lot of by-catch, including birds. So far, no pheromone lure is available, but methyl salicylate–a tree stress hormone–works as a lure.

Circle trap secured to a tree. Credit: Emelie Swackhamer, Penn State

PREFERRED HOSTS: TREE OF HEAVEN

Besides agricultural crops, the SLF eats more than 70 species of woody plants. Its favorite–used by late instar larvae and adults for feeding and laying eggs–is the tree of heaven, Ailanthus altissima.

The tree of heaven is an invasive species in its own right. Introduced in the U.S. at three separate times and places as an ornamental, its roots send out suckers that develop into new saplings, creating a stand of clone trees. The roots, especially of young trees and especially in the spring, emit chemicals that harm surrounding plants of other species. Although trees of heaven cannot invade a mature forest, they can creep in slowly from the edges. A mature female tree can produce over a million seeds per year. Salt-tolerant, the seeds even resist winter road salt that damages native oak and birch seeds. The tree of heaven seeds can germinate and establish even in highly compacted soil and in pavement cracks. After top-kill by fire or other physical damage, the trees can re-sprout from the roots, crown, or trunk. Seeds sprout after a fire as well. Tree of heaven establishes in early-succession, disturbed habitats.

Top: Tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) growing alongside Interstate Highway 75. Credit: Chuck Bargeron, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org. Middle 1: Tree of heaven in flower. Middle 2: Close up of the tree of heaven flowers. Bottom: A young tree of heaven. Credit for last three: Jan Samanek, Phytosanitary Administration, Bugwood.org

From a distance, trees of heaven can resemble walnut, pecan, or black walnut trees. Young trees may be mistaken for sumac. In the fall, though, the tree of heaven leaves turn yellow, not the brilliant red of sumac. The tree of heaven bark resembles the outside of a cantaloupe. Each leaflet has a lobe or two at the base, and the lobe has a bump on it. Broken-off leaves leave a heart-shaped scar. The most distinctive trait is that it smells like rancid peanut butter if you rub a leaf.

On the bright side, tree of heaven seeds stay dormant for less than a year, so at least the species does not build up a long-term seed bank. It is susceptible to Ailanthus Verticillium Wilt, a lethal vascular disease caused by the native fungus Verticillium nonalfalfae. The disease has a low off-target risk to native trees, which have evolved defenses to it. The fungus has a worldwide distribution, but in the U.S. is found only in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Legally, we cannot intentionally inoculate trees of heaven with the wilt unless it is found to occur naturally within our state borders, so V. nonalfalfae is another species for which to keep an eye out. Look for trees of heaven that wilt and die.

Tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) seedling. Credit: Leslie J. Mehrhoff, University of Connecticut, Bugwood.org

Needless to say, the NCDA recommends eliminating the tree of heaven and not using it as an ornamental plant. If you have trees of heaven, cut them down and grind or apply herbicide to the stumps so the trees do not regenerate new saplings. If you burn the trees, watch out for suckers or seedlings that may pop up later.

Chinaberry trees are a second preferred host and should also be eliminated, especially if SLF turns up in North Carolina.

PREVENTION

What can we do to prevent SLF from establishing in North Carolina? By reading this article, you have already started the first steps: educating yourself about the problem and learning how to identify SLF, tree of heaven, and verticillium wilt.

From here, consider:

- Share the information with others and scout for the pest and host.

- Make your property uninviting to SLF by removing trees of heaven and chinaberry.

- If you see a SLF in North Carolina, take a photo with a size reference such as a coin, kill the bug, and send the photo to badbug@ncagr.gov. They ask that you do NOT share it on social media until the NCDA investigation is complete and the identity is confirmed. The NCDA has a social media response ready to go when the species is found here.

The unexpected advent of SLF blindsided Pennsylvania. In North Carolina, we are learning from the past seven years of research and experience with the planthoppers in the U.S. That gives us a jump start in heading off this invasive species before it can gain a foothold here.

Want more?

- 6/30/22 Update: NC State University Extension Forestry: Spotted lanternfly confirmed in North Carolina

- Familiarize yourself with photos of the spotted lanternfly at all stages and in a variety of settings on Invasive.org. You can also find a plethora of tree-of-heaven images.

- See this Tree-of-Heaven and Spotted Lanternfly brochure (PDF) by the Washington State Department of Agriculture.

- Peruse Penn State Extension’s lengthy list of spotted lanternfly management resources.

- Watch an informative video presented by the NC State Extension.

Lead image: Adult Spotted Lanternfly. Credit: Lawrence Barringer, Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org