by Chris Smith, The Utopian Seed Project | Thursday, Dec. 3, 2020 –

As the executive director of The Utopian Seed Project, I’ve been working with Seed Savers Exchange, Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, and Working Food on a project to build a coalition of seed stewards, gardeners, farmers, chefs, and seed companies to preserve heirloom collard varieties and their culinary and cultural heritage.

There’s lots to love about The Heirloom Collard Project. Two highlights include:

- A Collard Week (Dec.14-17, 2020) of fantastic collard-focused presentations from people like Michael Twitty, Chef Ashleigh Shanti, and Ira Wallace.

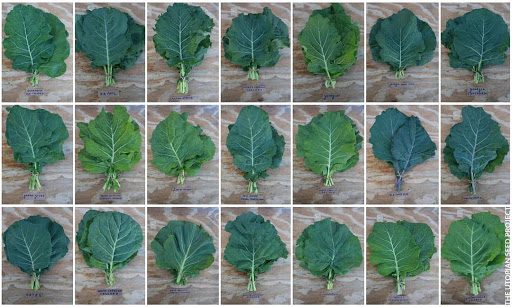

- A 20-variety collard trial happening right now, which includes more than 230 gardeners across the nation and eight farm trial sites growing all 20 varieties. (I’m one of the lucky eight to have all those collards in my field!)

Now, I could tell you about all the wonderful collards we’re working with and recount the wonderful stories of some of those heirloom collards, but I feel this is a show, don’t tell situation. I want you to really understand the excitement behind this project, and to do that, I’ll have to take you to the edge of a rabbit hole and push you down. You may get lost in the labyrinth and not even finish this article. It’s possible you won’t emerge for many days, perhaps weeks, but when you do, you’ll have a new appreciation of the diversity of collards.

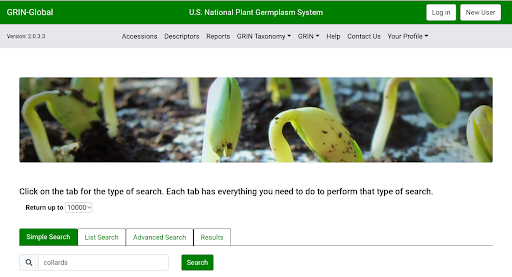

The rabbit hole of which I speak, this labyrinth, is our very own, tax-payer funded, Agricultural Research Service managed Germplasm Resources Information Network. If you’ve been there before then you may know what to expect. If this is your first time, then I suggest you make yourself a collard and gin-based cocktail and open your mind. This could be a blue pill or a red pill moment.

It all starts with a simple, innocuous search for ‘collards’, a word most likely bastardized from the old English, colewort. While multiple origin theories exist for how collards arrived in North America, it is the northern Europe (probably England) origin story that seems most likely.

Press ‘Search‘!

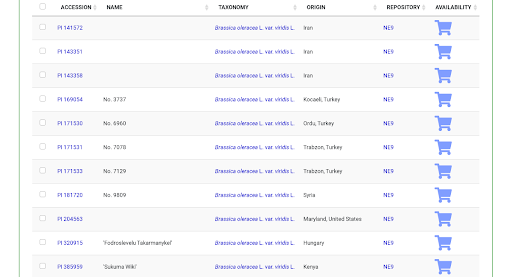

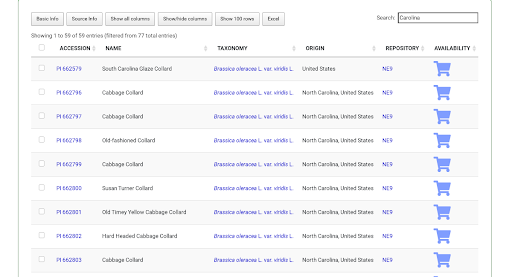

A list of 77 collard entries comes up, showing us the taxonomic designation of Brassica oleracea L. var. viridis L. This is the official way to say collards and, in this case, the ‘var. viridis’ part is important. Brassica oleracea alone describes a species that includes cabbage, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, kohlrabi, and kale. Interestingly, if you search for ‘collard’ instead of ‘collards’ then you can easily get lost down a different rabbit hole.

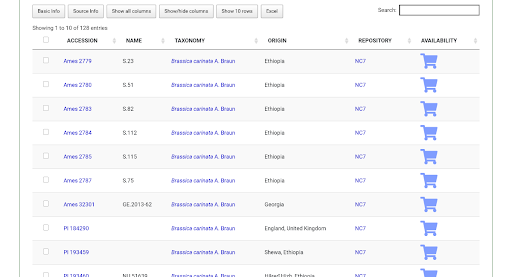

Note the long list of Brassica carinata with a strong skew towards Ethiopian origin. The origin column is not actually a botanical origin but the original source of the seeds. Brassica carinata is known by many names, including Ethiopian Kale, African Kale, but also Mustard Collard, which is perhaps why it shows up in this search. That said, I have no idea why it shows up for a ‘collards’ search and not a ‘collard’ search (a glitch in the matrix), but it does highlight the importance of taxonomy!

If we go back to our ‘collard’ search, we can add search terms in the upper-right search box. I choose ‘Carolina’:

This is where things can get fun. I choose ‘Carolina’ because it does a good job of bringing up all the collard seeds that were collected in North and South Carolina.

You can try filtering by anything. I tried ‘Buncombe’, which is the county of N.C. where I live, and ‘Asheville’, but it yielded no results. It’s a shame because culinary historian, Dr. David Shields has been searching for a lost collard variety called N.C. Buncombe Short Stem collard, which was sold by an Asheville-based seed company in 1920. Funnily enough, that seed company was located just down the road from where Sow True Seed exists today! Warning: Exploring old seed catalogs is a completely different but equally dangerous rabbit hole.

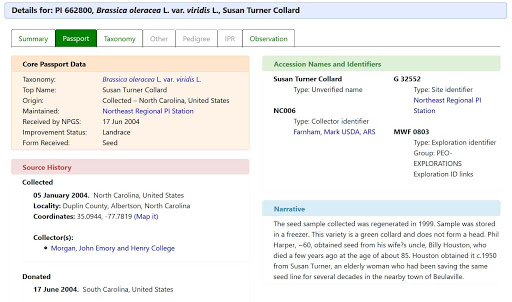

Scrolling through the list of wonderful names of collards collected in South and North Carolina, the Susan Turner Collard leaps from the page. This is mainly because my mum is called Susan, and she keeps a large vegetable garden in England. I’ve been joking with her about starting a garden with only Susan-inspired varieties. I have a tomato from Craig LeHouillier called Dwarf Sue; Yanna Fishman gave me a garlic simply called Susan; and now there’s a collard called Susan Turner! I’m sure certain collards will speak to you too. Once you find one, click on its ‘Accession Number‘ (i.e., G32552 or PI662801) for more information.

Sometimes you get lots of details, sometimes not so much. I always like looking at the narrative under the ‘Passport’ tab. We learn that Phil Harper was the most recent seed saver (Harper happens to be my mother’s maiden name) and this collard is named for the original seed keeper, Susan Turner. My American geography isn’t great and I don’t know where Duplin County is, so I click the ‘Map It’ link.

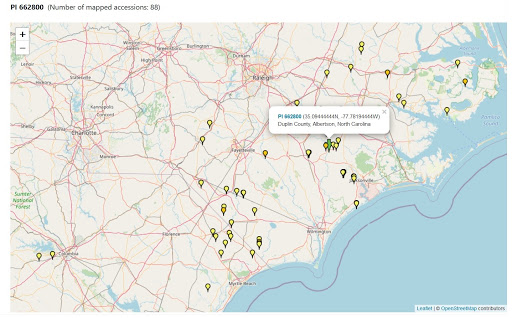

Now I know where Duplin County is! But look at all the other pins. This is the span of collard varieties across North and South Carolina held by the USDA. Most, if not all, are from seed collecting expeditions conducted during the 1990s and early 2000s which culminated in a wonderful collection of collards and a very interesting book, Collards, A Southern Tradition from Seed to Table by Edward Davis and John Morgan. Take a look at the Susan Turner Collard screenshot above and note the ‘Collector’ is named Morgan.

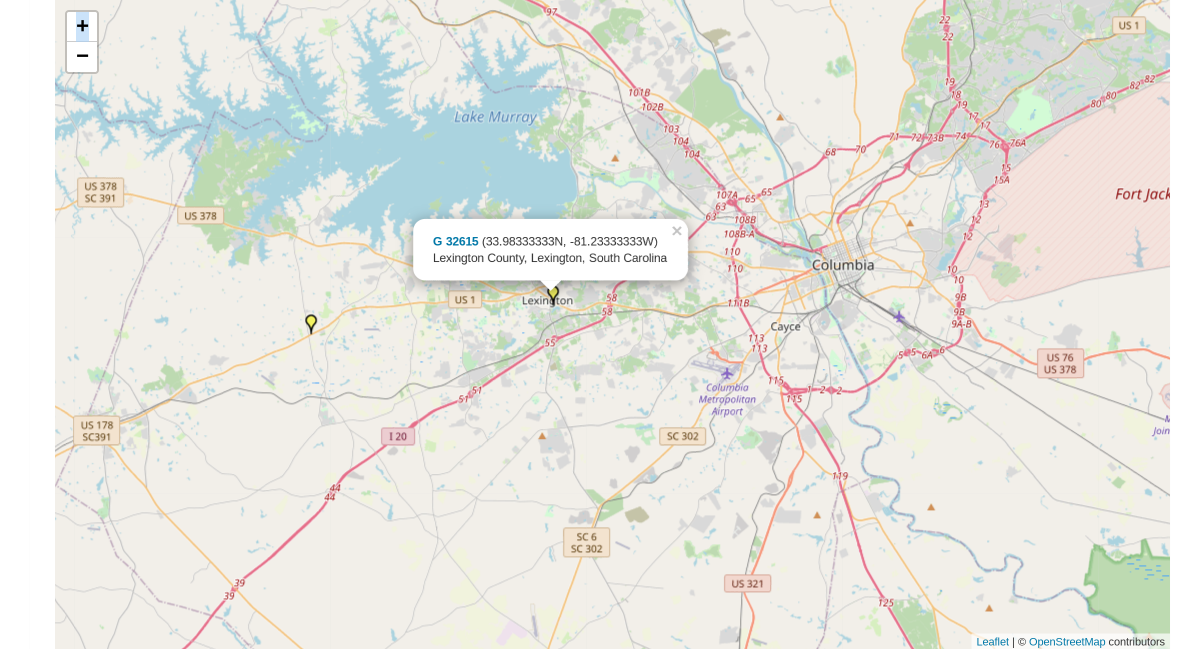

I notice there are a couple of collard varieties collected close to where my wife grew up, in Columbia, S.C. I zoom in on Columbia and there is a pin right over Lexington S.C.

My wife’s grandmother, Ellen Verner Scoville, lived in Lexington and died a couple of years ago at the age of 99. The pins are clickable, which takes you to the variety’s main page.

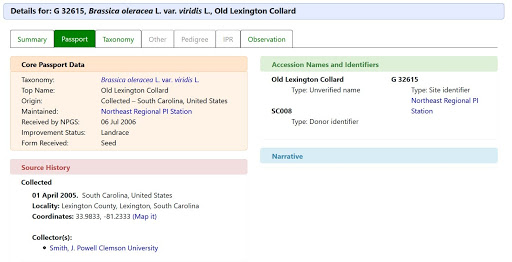

It turns out G32615 is named Old Lexington Collard. Growing Old Lexington Collard would be a fun way to remember Ellen! Sadly there is no narrative. This is not unusual and many of the entries are incomplete. However, for the scientific amongst us, you can click on the ‘Observation’ tab.

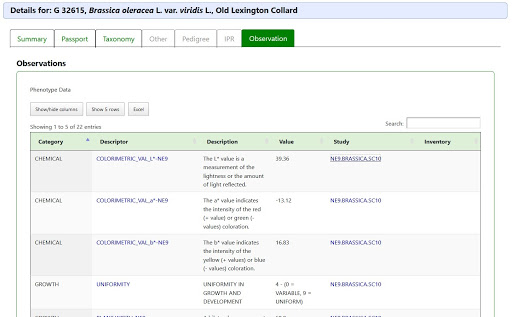

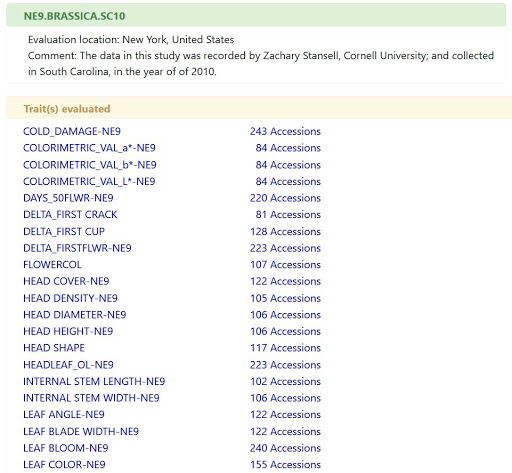

Under ‘Observation’, I see that 22 phenotype traits have been evaluated. You can search through the values for this one variety, but there is also a link to the study that evaluated those traits: NE9.BRASSICA.SC10. Since I’m growing lots of varieties, there is a chance that the study evaluated some of the varieties that I’m growing.

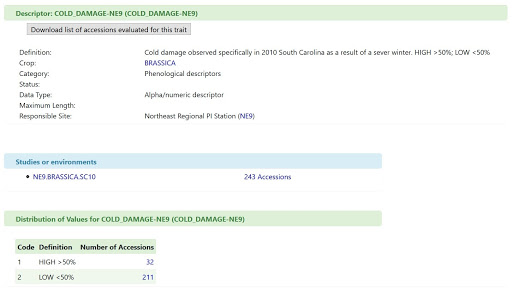

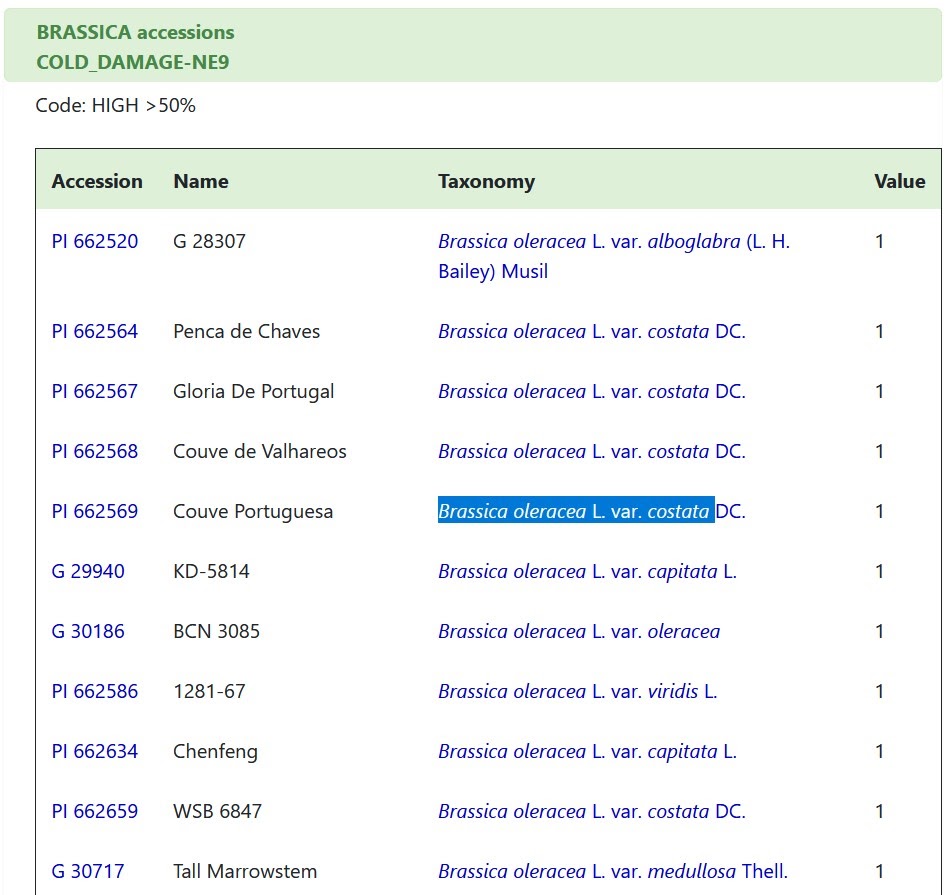

The first one, Cold_Damage-NE9, is immediately interesting to me. I’m growing in Western NC where it can get cold enough to kill collards, so identifying some super cold-tolerant varieties would be useful.

As I click for more information, it’s a little disappointing; the evaluation criteria lacks details. All we know is that the collards were assessed during the severe winter of 2010 in South Carolina and that the collards were categorized as high or low, based on 50% more/less cold damage. We don’t know how much cold damage or at what temperatures. The dataset shows that most collards (211 out of 243 accessions) suffered low damage, which is not surprising for collards grown in South Carolina. (even for a severe winter). Given that I’m growing 20 collard varieties, and we’ve already had lows of 17F (and it’s sure to get colder), I’m intrigued to scan the list of the 32 varieties that suffered high cold damage to see if I can expect any early collard death in my trial!

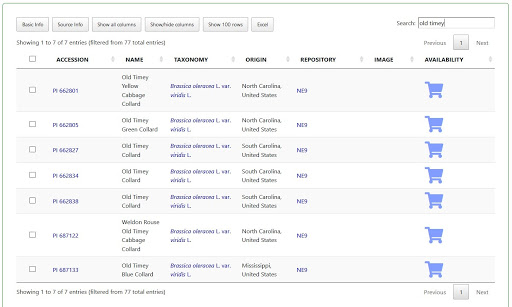

The list of 32 accessions that suffered greater than 50% cold damage shows a lot of non-collard Brassicas. It’s clear that the study was evaluating a wide range of Brassica oleracea. A quick scan of the list only shows a couple of easily cold-damaged collard accessions (which fits with what we know about the cold tolerance of collards), and none of them are in my trial! I notice that two of the collards listed have Old Timey in their title:

They jumped out because one of the varieties in my trial is Old Timey Blue, and I love it!

It made me wonder how many Old Timey varieties are out there, so I go back to the original ‘collards’ search page and filter results by ‘Old Timey’ instead of ‘Carolina’.

In the results, I find there’s an Old Timey Yellow Cabbage Collard from North Carolina. And down another rabbit hole we go! But I think it’s time for you to go down your own rabbit hole. And while you’re getting lost down there, remember how incredible GRIN is and how important the preservation of genetic and varietal diversity is for our food system.

If you’re committed to hybrids, then this is where plant breeders look to begin the creation of new varieties. If you love the preservation of old-time heirlooms, then many are hiding here (The Utopian Seed Project unearthed a conch pea of superior taste and has since boarded that variety onto the Slow Food Ark of Taste). If you are concerned about massive biodiversity loss, then GRIN offers some insurance for the future. If you’re crazy about collards, then the reason The Heirloom Collard Project exists is because of our access to the GRIN. Luckily we’ve done some of the work for you in this regard, so if you want to dive deeper into collards without venturing into GRIN then check out The Heirloom Collard Project and be sure to tune in for some great virtual presentations on collards during Collard Week.

A note about GRIN

GRIN is not a seed catalog with free seeds; it is a Germplasm Resources Information Network. It is an incredible resource that should be respected and seeds should only be requested in compliance with their distribution policy.

About the Chris Smith

Chris Smith is a father, seed saver, and gardener who loves to write. He is the executive director of the Utopian Seed Project, a crop-trialing non-profit working to celebrate food and farming. His book, The Whole Okra, won a James Beard Foundation Award in 2020. He is also the co-host of The Okra Pod Cast. More info at Chris’ website and at his organization, The Utopian Seed Project.

All images courtesy of Chris Smith.