by Mark Dempsey, CFSA’s Farm Services Coordinator

With August now upon us, many growers across the Carolinas are preparing for fall crops – if they haven’t already started them in the greenhouse in the western parts of both states. Brassicas, a.k.a. cole crops, are staple fall crops among many vegetable growers because they generally command a good price at market and are popular for their nutrient density, impressive crop diversity, and culinary flexibility. Brassicas grown in the Carolinas include crops with flowering heads (broccoli & cauliflower), fattened stems and/or leaves (cabbage, Brussels sprouts & kohlrabi), leafy greens (kale, collards, choi & mustard), and roots (turnip & rutabaga). Fall-grown brassicas are especially popular because the end-of-season cold weather can sweeten them up and reduce insect pressure, making them tastier and sometimes easier to manage. But nailing down their management isn’t always easy. Below are several tips for growing a bumper fall brassica crop:

1. Timely establishment:

Getting the timing right is one of the most important aspects to a good fall crop.

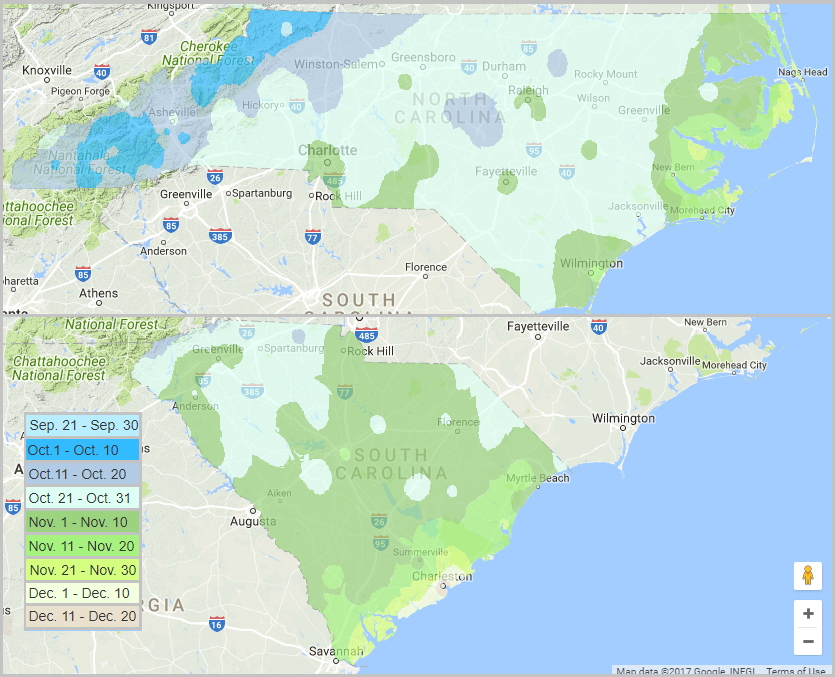

Getting the timing right is one of the most important aspects to a good fall crop. Brassicas are cool season crops that don’t like it hot, but don’t like it too cold either. The heat of a Carolina summer is too much for most brassicas, turning them bitter, so most are grown either before or after the heat. However, because a sudden hard frost or a deep freeze can be damaging, it’s important to hit the cool window of fall just right, starting brassicas once the weather starts to cool to avoid heat stress (July – Sept depending on location and crop), but with adequate time to mature or go to market before winter sets in. It’s common to determine planting date by using days-to-maturity of a crop (provided by seed vendors) to count backward from average first frost or freeze dates, or from a later date depending on the crop’s cold tolerance. Field plantings are typically done with greenhouse-grown transplants (4-6 weeks from sowing to transplant), although early plantings of heat-tolerant crops/varieties (ex. collards or broccoli) can be direct-seeded successfully as well. Planting at least two successions (approximately 10 days apart) is highly recommended to have a marketable product for longer, and reduce risk of crop loss or failure. Three plantings is even better. Use the map (Figure 1) and Table 1 below to help determine planting date.

Figure 1. Approximate average first frost date throughout the Carolinas from data organized by zip code. Note that frost date zones do not exactly follow plant hardiness zones because frost zones represent a narrower range of time (10 days vs several months).

Modified from:

http://www.plantmaps.com/interactive-north-carolina-first-frost-date-map.php

http://www.plantmaps.com/interactive-south-carolina-first-frost-date-map.php

Other high quality climate mapping sites may also be useful, such as: http://www.prism.oregonstate.edu/normals/

Table 1. Common start dates for fall brassicas organized by east/west region of each state. Data modified from 2017 Southeastern U.S. Vegetable Crop Handbook (Southeastern Vegetable Extension Workers Group).

|

July |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

||||||

|

Crop |

Location |

1-15 |

16-31 |

1-15 |

16-31 |

1-15 |

16-30 |

1-15 |

16-31 |

|

Broccoli |

Western NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eastern NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Western SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Eastern SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cabbage |

Western NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eastern NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Western SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Eastern SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Cauliflower |

Western NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eastern NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Western SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Eastern SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Collards |

Western NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eastern NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Western SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eastern SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Kale |

Western NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eastern NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Western SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eastern SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kohlrabi |

Western NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eastern NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Western SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eastern SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Brussels sprouts |

Western NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eastern NC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Western SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Eastern SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Avoiding insect damage:

Avoiding or staying ahead of the bugs is the second key to a good crop. Flea beetle, harlequin bug, cabbageworm, and often aphids and root maggot are the main pests; cabbageworm is a loose term used for cabbage looper, imported cabbage worm and diamondback moth – so keep an eye out for all three. Note that some management techniques apply to all pests, while other techniques are pest-specific. First, insect pests can be avoided by putting time and space between brassica plantings, for example by not planting a summer brassica, and possibly even a spring brassica, and also controlling brassica weeds. Row cover can go a long way as well. Cultural techniques such as growing certain crops/varieties resistant to your problem pest, or growing a sensitive crop/variety as a trap crop (killed once the pest is present with, for example, a flamer). Insect pests can also be avoided by delaying planting, as pressure becomes less intense as weather cools. Biocontrol by hungry (i.e., insectivorous) and parasitic insects can be helpful, but typically require nearby habitat; farmscaping – the practice of growing a diversity of cultivated and wild plants in and around the farm – can be helpful for reducing pest pressure in brassica crops, and is recommended as a general practice if manageable. In the case that avoidance and biocontrol techniques don’t reduce pest pressure to an acceptable level, then a few organic pesticides may prove helpful as a second line of defense. These products include kaolin clay, pyrethrin, neem oil and Bt products.

If flea beetle is your problem pest avoid choi and mustard, possibly opting for kale and collards, which are generally more resistant (lacinato kale typically most resistant). Kaolin clay can help a lot with flea beetle infestations, but must be applied thoroughly and frequently. Pyrethrin & neem oil products can also be used successfully, but be familiar with their modes of action before use: pyrethrins knockdown insects by affecting their nervous system, and aren’t growth stage-dependent, while neem interferes with hormones involved in growth and molting, and doesn’t work as well on adults as larvae.

If harlequin bug is your pest early prevention or control is key. Row cover over cash crops, and timely termination of trap crops (mustard in particular) is recommended. If possible remove residue of previous crops, especially brassicas, where harlequin bug overwinters. Biocontrol is limited because they have several chemical defenses against other insects, but there are a few wasps that parasitize harlequin bug eggs; parasitization rates range widely (10-60% of eggs), so anticipate using chemical control if the first two methods are unsuccessful.

Cabbageworms, aphids and root maggot tend to prefer cabbage, so if pressure is high from any of these pests it may be best to avoid cabbage. These pests also feed on other brassicas, of course, and growing resistant crops/varieties is helpful; select varieties with glossy leaves if possible to deter leaf-feeders. Bt products are very helpful for protecting against cabbageworm feeding, and are only effective on larvae.

3. A solid soil fertility plan:

Finally, good fertility management will give you good crop growth, and an inherent ability to resist insect and disease pressure. Brassicas have a relatively high nitrogen (N)-demand for maximum yield, but are flexible with N-use; yields correlate with available N. Typically 160 lb total N/a is recommended for flowering/heading types, with less N recommended with decreasing plant size (least N for kale, for example). Some N can be credited from previous legume crop or from residual soil N, although be careful to get a handle on N management on your farm before choosing to apply less N. Testing for other soil nutrients (phosphorus, potassium & boron are most important) at a state or private lab is essential for proper nutrient management; deficiencies in these will limit growth and resistance to pests, and ultimately reduce yields. Soil high in organic matter, particularly with high biological activity, have been reported to result in greater pest resistance of crops and higher yields.

Finally, good fertility management will give you good crop growth, and an inherent ability to resist insect and disease pressure. Brassicas have a relatively high nitrogen (N)-demand for maximum yield, but are flexible with N-use; yields correlate with available N. Typically 160 lb total N/a is recommended for flowering/heading types, with less N recommended with decreasing plant size (least N for kale, for example). Some N can be credited from previous legume crop or from residual soil N, although be careful to get a handle on N management on your farm before choosing to apply less N. Testing for other soil nutrients (phosphorus, potassium & boron are most important) at a state or private lab is essential for proper nutrient management; deficiencies in these will limit growth and resistance to pests, and ultimately reduce yields. Soil high in organic matter, particularly with high biological activity, have been reported to result in greater pest resistance of crops and higher yields.

With these things in place you should be able to raise a good brassica crop this fall. Careful attention to planting windows, the presence of pests, and soil fertility management will pay off with a good fall and winter harvest. For more information on fall brassica production contact Mark Dempsey.

Are you considering using conservation practices such as integrated pest management, fertility management, low-till, or mulches, and want financial assistance to do so from the USDA? If you’re also transitioning to certified organic production you should consider a Conservation Activity Plan Supporting Organic Transition (CAP 138). CFSA can help write these conservation plans after approved by the NRCS. Visit for more information on how we can help you!