Background

Achieving and maintaining organic certification can often be a daunting prospect for producers, and a specific set of requirements must be met before they ever apply.

To be officially certified as organic, products must be grown and processed according to federal guidelines that address soil quality, animal husbandry practices, pest control, additives, and more. Produce must be grown on soil that has had no prohibited substances, including most synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, applied for three years before harvest; for organic livestock, animals must be fed all-organic feed, not administered antibiotics or hormones, and raised in natural living conditions.

However, certified organic producers face pressure on the supply and demand side of production. Becoming certified organic is often expensive, takes several years to achieve, and requires higher labor costs than conventional farming.

To navigate the process, local, state, and federal organizations engage in specific outreach efforts to get straightforward, free resources to producers. This article explores some of the existing educational resources available and identifies areas for improvement in ongoing organic education outreach.

Existing Education Resources

With the continued proliferation of organic farming, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) website has greatly expanded their available resources for producers exploring or seeking to maintain certification. The National Organic Program features a landing page and FAQ section for producers interested in organic certification and is divided into basic and advanced sections.

The online Organic Literacy Initiative, launched via a 2011 USDA working group, provides producers with detailed information about organic agriculture and the programs and services USDA offers to support it. The resources include a resource guide that outlines how each USDA agency supports organic agriculture and contact information, an Organic 101 training module about what organic means and how certification works, and a factsheet that contains information about organic standards and certification.

Land grant universities supplement existing USDA outreach by offering a combination of educational outreach and technical assistance. Clemson University, for instance, operates a USDA Accredited Certifying Agent through its Department of Plant Industry, as well as providing a resource hub for producers exploring the viability of organic certification. The Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program (SARE) also provides a variety of competitive grants for education and outreach activities that support sustainable agriculture systems, many focusing on organic production and marketing.

Risk management education and outreach partnerships from USDA’s Risk Management Agency also ensure that producers get the information they need to effectively manage their risk through difficult periods and remain productive.

Non-profit organizations at the state, regional, and federal level also provide organic certification consulting for conventional farmers transitioning to certified organic, beginning farmers interested in organic certification, and farmers interested in using organic production practices in general. These resources include on-farm visits, transition and production handbooks, and more.

CFSA Survey on Organic Education

Primary Information Source

Carolina Farm Stewardship Association conducted a survey among 129 North and South Carolina producers to collect feedback on the organic certification process, as well as the overall accessibility of resources that support producers’ certification journey.

The majority of respondents (33%) get their information directly from private certifiers. 23% of respondents identified state extension agencies as their primary source for organic resources and information. 19% rely on technical assistance from non-profit organizations, tied with 19% who use information directly from the USDA’s website, and 14% use recommendations and referrals from fellow producers.

Note: There is some overlap between state extension agencies and private certifiers, as Clemson University is a USDA Accredited Certifying Agent, and some respondents selected both.

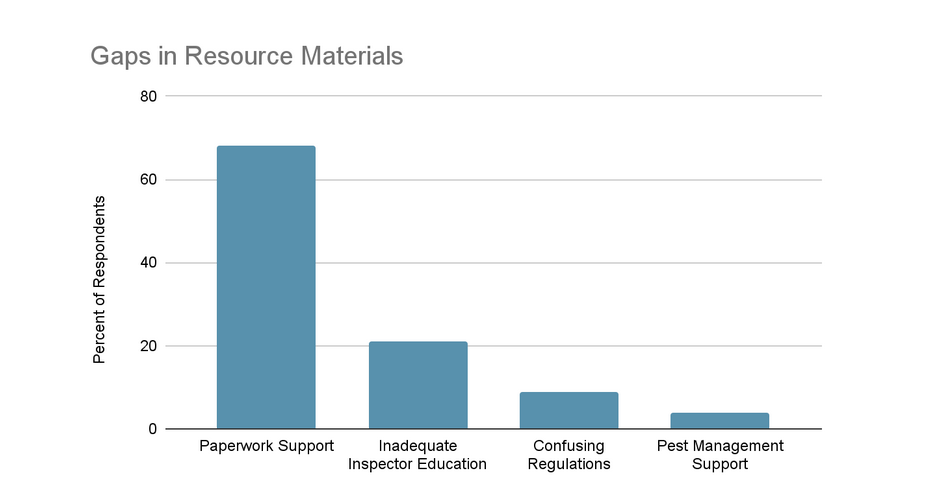

Gaps in Resource Materials

While producers acknowledged a wide range of access to information regarding the organic certification process, 66.7% of producers identified the time-consuming nature of required paperwork as surprising and a barrier to maintaining or achieving organic certification. 21% of respondents stressed a gap in organic training among inspectors themselves, citing undertrained or uninformed inspectors as a barrier to organic certification. 9% cited confusing language around the regulations themselves, specifically around washing, packing, and processing, and 4% cited a need for more resources on best management practices for pest management.

Overwhelmingly, frustration and confusion around the paperwork required to achieve and maintain certification is one of the largest complaints from producers. Certified operations must keep records that detail their production practices, including production, harvesting, and handling of their agricultural products, and must be made available for review by certifying agents. For new producers or nonorganic producers transitioning to organic, this paperwork often comes as a shock, requiring much more intensive documentation than standard farming practices.

For instance, a mandatory Organic Systems Plan (OSP) requires detailed documentation of harvest, tillage, livestock management, and all amendments used, along with date and precise location of application. Activity logs require a detailed record of any farm activities, including irrigation, mowing, weather, and more. Compost production records require a meticulous outline of how compost-production processes satisfy the required regulations. Equipment cleaning logs require documentation of method and frequency of cleaning farm equipment to ensure nonorganic products do not contaminate organic crops. Producers must also complete buffer crop disposition records, indicating what happens to crops that are grown on buffer land that is organically managed but may be exposed to a risk of outside contamination.

Altogether, this paperwork is time-consuming enough that a full-time staffer could struggle to keep up, but most small and mid-sized producers face the daunting task of managing it themselves, in addition to the daily rigors of farming.

Many resources currently exist from the National Organic Program, state extension agencies, and nonprofits that outline the paperwork required, but producers still identify paperwork as a prohibitive burden to certification and would likely benefit from a walkthrough on easy recordkeeping schedules and efficient logging.

An irony in researching the existing gaps in organic research materials was that, when asked about improved access to resources, many of the respondents identified inconsistent inspectors as most needing access to better training materials. Developing a method of standardizing training and compliance will continue to be critical for pending organic producers to have a clear and actionable path to certification.

Several respondents identified confusion around the language of organic regulations themselves, and as one producer specifically cited, around “translating washing/packing/processing regulations, as they are meant for larger producers and thus confusing (for smaller producers).” Producers may benefit from scale-specific guides and resources to help them navigate the respective regulations relevant to the size of their operation.

Summary

While there continues to be a wealth of resources on the organic certification process available to producers, the amount and time-consuming nature of paperwork required to achieve and maintain certification continues to be daunting and is routinely cited by producers as the primary barrier to certification.

Outreach for new and existing organic producers should emphasize a streamlined approach for guiding producers through the required recordkeeping process, as well as a continued push for improved training among organic certifying agents.

A downloadable version of this document is available here.

This whitepaper was supported through the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Transition to Organic Partnership Program (TOPP). TOPP is a program of the USDA Organic Transition Initiative and is administered by the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) National Organic Program (NOP).

About the Author

Matt Kneece is CFSA’s policy director, which oversees CFSA’s advocating for state and federal policies that better support local food, organic farming, and resilient regional food systems. He works closely with CFSA members and allies to educate policymakers on issues of importance to the local, organic farming communities and spearhead grassroots communications in support of specific policy needs.

A native of South Carolina, Matt combines a background in governmental affairs and public policy with a passion for sustainable agriculture to serve as CFSA’s policy director.

Read more about Matt in his staff Q&A!

Photo credit: all photos taken by Stacey Sprenz at the Scale-Appropriate Equipment for Increased Efficiency & Mechanization on Small Farms workshop held at Open Door Farm, Cedar Grove, NC, during CFSA’s Sustainable Agriculture Conference, 2023.