By Chloe Johnson CFSA Local Produce Safety Coordinator | Monday, Feb. 11, 2019 –

The personal nature of local, sustainable farmers markets allows customers an opportunity to ask questions about growing practices—trust is built between buyer and seller. The short supply chain—less distance between “farm and fork”—increases consumer confidence in the quality and safety in the produce sold at farmers markets.

The more foodborne disease outbreaks that occur, however, and the more media coverage those outbreaks get, the more skepticism farmers may receive from customers. I’ve seen this first-hand. Last year, when the romaine lettuce recall was nearing its end, I had a new farmers market customer comment on the current dangers of lettuce. Though her friend had expressed interest in my Salanova mix (I wasn’t selling romaine), my explanation of the variety I had – and the fact it had been grown 30 miles from where we stood – did nothing to change her attitude. Neither potential customer bought lettuce from me. I started to wonder then how I could best educate farmers market customers about food safety practices so that needless anxiety didn’t spread.

National foodborne disease outbreaks threaten our local economies when customers cannot parse out how risks are assessed or addressed.

What do studies show?

I was thinking about this around the same time Penn State Extension published a study looking into food safety culture at farmers markets in Pennsylvania. The authors of the study observed vendors and found that food safety practices were used inconsistently and ineffectively by the majority of the observed vendors.

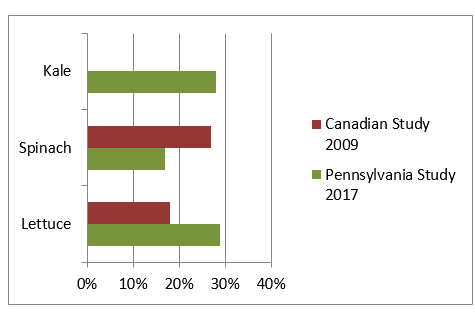

A few studies referenced by the Penn State Extension study found that leafy greens purchased from local farmers markets in Pennsylvania and Alberta, Canada tested positive for the presence of E. coli, as illustrated in the chart below (chart source).

Some studies have found the presence of E. coli and other pathogens on leafy greens sold at farmers markets. Findings indicate that even small farmers with direct to consumer market channels should be aware of and responsive to food safety risks.

It is important to note that there are many types of E. coli, some of which are actually beneficial to humans. However, tests for the presence of E. coli are, currently, the best indicator we have to discover potential fecal contamination. Neither study found any presence of E. coli O157:H7, the extremely toxic bacteria that has been implicated in several foodborne disease outbreaks. These studies only point to potential food safety hazards.

Since 2006, approximately 34% of E. Coli O157:H7, 27% of Listeria, and 34% of Salmonella outbreaks investigated by the CDC have been traced back to fresh produce. Recent research identifies that, in many cases, the causes of produce contamination is manure, wildlife, or worker hygiene.

As an example, in 2011, strawberries purchased from a small farm located within the US transmitted E. coli O157-H7 to at least 16 people. The strawberries were most likely contaminated by deer droppings in the field. In this incident, four of the sick individuals were hospitalized, two underwent dialysis as a result of developing a complication from the infection, and one person died.

The root of the big 2006 spinach outbreak (205 sick, three deaths) was thoroughly investigated, and researchers concluded that the two possible contaminants were either

- Feral pigs running through the field, or

- A nearby pasture-based cattle operation.

The cattle operation was less than a mile from the spinach fields, but not directly adjacent. Manure from cattle was thought to have first entered surface waterways that then contaminated the well that was used for irrigating the spinach fields. Either of these contamination sources could occur on many farms across the U.S., regardless of the operation’s size.

As these examples show, potential outbreaks are not directly related to the size of the farm.

In fact, the CDC defines an outbreak as “when two or more people get the same illness and investigation shows it came from the same contaminated food or drink.” Small outbreaks rarely get national attention, and we can assume many go unreported. All farms share the same public health risks. It is true that shorter supply chains lower that risk, but it doesn’t entirely eliminate it.

The Penn State Extension study heavily focused on the use, or lack of use, of gloves. What the study did not explain was that gloves are not a substitute for handwashing. In fact, under GAP standards, if the farmer incorporates gloves into their food safety program, hands must be washed prior to putting the gloves on, and then discarded any time handwashing would otherwise be required. Putting on gloves is, one might argue, better thought of as a practice to protect one’s hands (or to cover a bandaged wound) than as a way to protect produce from unclean hands. Gloves may become torn or, just like hands, contaminated.

What about at the farmers market?

Farmers markets present unique food safety challenges, as they are usually held outdoors and in once-a-week or temporary locations. These limitations, coupled with the demonstrated risks illustrated by the studies referenced above, add food safety practices to the list of topics farmers must educate customers about. The burden is on vendors to demonstrate at market that we are aware of and responsive to contamination risks for fresh produce.

Farmers can demonstrate their commitment to providing safe produce by:

- Leaving stands to wash hands if bare hands were contaminated in some manner (e.g. touching the bare ground or dirty bins, sneezing, or eating).

- Not allowing workers who are ill to work markets, but finding other non-produce handling tasks for them to complete.

- Pre-packing produce so that bare hands (vendors or customers) do not contact loose, uncovered produce.

- Stacking bins so crates holding extra produce aren’t in direct contact with the ground.

Contamination risks are reduced through proper handling of produce and implementing good health and hygiene policies.

We in the food safety world are fond of reminding people that hands are a food contact surface (along with, for example, the tables in your packing shed). Multiple people handling bare produce, and cell phones or money, do not realize that these items are a potential source of cross-contamination. Paper money hasn’t been scientifically proven to be a transmitter of foodborne pathogens, but there is a strong, and possibly justified, the perception that it is “dirty.” Cell phones are well-documented as harboring a lot of germs, but neither have they been implicated in a foodborne disease outbreak. Nevertheless, it is a best practice to develop systems that separate financial transactions (whether paper money or using your phone) from handling fresh produce.

What can small farms do?

Farmers can also reassure their local market customers about food safety concerns by developing a Food Safety Plan (FSP). These documents can go a long way in helping farms to identify potential risks and take steps to alleviate them. If customers express concern about food safety, you’ll have a concrete program you have implemented to tell them about. Writing a FSP puts you ahead of the curve, too, if you later decide to become GAP certified. As awareness of foodborne disease outbreaks continue to rise, being GAP certified might become valuable to your customer base.

An integral first step in any food safety plan is evaluating on-farm risks, including those presented by adjacent and nearby land and wildlife (such as the two sources of contamination found in the examples noted above). In the event of a future foodborne disease outbreak, take this opportunity to educate customers about your demonstrated commitment to food safety, in turn, that customer will have more appreciation of you and your business practices.

The strongest conclusion drawn from the Penn State study was that farmers were aware of food safety issues, but may not be applying that knowledge. The study used secret shoppers to observe vendor behavior and found that some individuals were not using proper food safety practices. This indicates that farmers acknowledge the importance of food safety but need to develop a stronger familiarity with best practices to help develop a food safety culture on farm and at the market.

Basic attention to food safety best practices can go a long way towards assuring your customers their health and safety is part of your mission. Food safety audits are often used as a marketing tool. Farmers markets enjoy a reputation for providing high-quality, fresh, healthy produce; continued attention to food safety practices will protect that reputation.

Questions? Want hands-on help?

Drop Chloe an email or give her a call at (919) 542-2402.

Chloe and the rest of CFSA’s Local Produce Initiative Team are available for one-on-one consultations with members about food safety issues—from the farm to market. They can provide guidance on potential risks, best practices, writing a food safety plan and even help prepare for a GAP audit.