by Mark Dempsey, CFSA Farm Services Manager | Thursday, Dec. 16, 2021 —

Winter cover crops approaching termination time

This fall, we completed the second year of CFSA’s organic no-till project determining production costs, yields, profitability, and scalability of growing no-till butternut squash after a cereal rye cover crop. We used several cover crop and weed management methods that were implemented using a tractor, walk-behind tractor, or done manually.

If you aren’t familiar with cover crop-based organic no-till, the premise is to grow a large cover crop, such as rye, lay it down as a mulch by crimping or mowing, plant your cash crop into it, and rely on the cover crop mulch to suppress weeds. It is effectively a “grow your own mulch” production system. But many questions remain about the best termination method to kill the cover crop, how well the resulting mulch suppresses weeds, and the scale at which it makes financial sense to use a tractor, a walk-behind tractor, or manual methods.

For a thorough explanation of our research questions, methods, and first-year results, see our write-up from earlier this year.

For a brief overview of our methods:

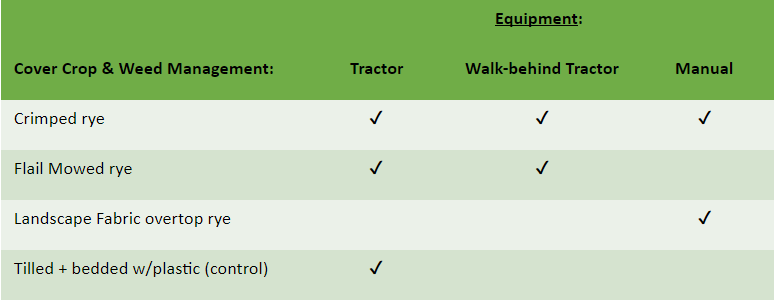

We grew a cereal rye cover crop for two consecutive seasons at two locations, followed by no-till butternut squash. Rye was terminated in May once it began to develop seed (“water ripe” growth stage) using different termination methods (flail mowed and crimped) that were driven by equipment or done manually. A subset of plots were covered with landscape fabric for season-long weed suppression. Butternut squash was manually transplanted into the resulting mulch or landscape fabric. Finally, we tested these treatments against the organic industry-standard: tilled and bedded with plastic mulch. Treatments were as follows:

All treatments were implemented in full at Lomax Farm (Concord, NC) both years. A subset of treatments were implemented both years at Red Scout Farm (Black Mountain, NC): only no-till treatments using a walk-behind or done manually.

The performance of each system was measured by:

- Production cost (equipment + labor + materials, fuel and maintenance)

- Yield

- Profitability

- Scalability (i.e., how production cost and profitability increase with acreage across treatments)

An important note on scalability regarding total production costs: in this analysis, scale-dependent costs (i.e., those that increase with increasing acreage) included labor, materials, fuel & equipment maintenance. Fixed costs (i.e., those that are the same regardless of acreage) included the annual costs to own equipment (i.e., purchase price minus resale value divided by the number of years it’s owned). This captures the dynamic trade-off between upfront costs of equipment and money saved by the economies of scale achieved by it (i.e., faster ground speed and wider working width).

The Main Takeaways

While results are essentially the same as last year, with a few minor updates, the second year of data bolstered findings from the first year and allowed us to test for differences among treatments using common statistical techniques (mixed model ANOVA). The results:

1. Weed pressure and the resulting time spent weeding is a primary consideration when taking on cover crop-based no-till (Figure 1).

- Time spent weeding dominated total management time for crimped and mowed treatments but not landscape fabric or tilled treatments.

Figure 1. Total management time (hours/acre) divided into five management categories. Error bars are standard error of the mean (total hours); n=2 site-years for Tractor-based treatments; n=4 site-years for all others.]

2) Weed management drove the cost of labor in crimped and mowed treatments, which, in turn, was a significant portion of total production costs (Figure 2). In fact, weed management accounted for 25%-45% of total costs among crimped and mowed treatments because weeding was performed manually and was not mechanized.

- Time spent weeding was consistently higher in mowed vs. crimped treatments (by 53%).

- Total production costs highlight the utility of landscape fabric for reducing weeding time and also highlight the need for mechanized weed control (i.e., high-residue cultivation) where possible.

- If you already have a flail mower, plan to follow mowing with a persistent mulch for better weed suppression (thick straw, landscape fabric, or similar).

Figure 2. Total annual production cost ($) for one acre of butternut squash, broken into three components: labor, materials, fuel and maintenance, and equipment. Error bars are standard error of the mean (total cost); n=2 site-years for Tractor-based treatments; n=4 site-years for all others.

3) When considering how each treatment scaled up in acreage (0.1 to 10 acres), several treatments stood out (Figure 3):

- Applying landscape fabric over the crimped rye was the cheapest treatment to implement up to about 3.5 acres. That is, the extra cost (labor and materials) to apply and remove landscape fabric was more than made up for in saved weeding time, compared to all other treatments (up to 3.5 acres).

- Using a manual crimper–a very simple device that can cost just a few dollars to make (Figure 4A) – was the second cheapest to implement, up to about 3 acres. Manual treatments are cheap to implement at low acreages because they don’t require investment in costly equipment but become more expensive than mechanized options at higher acreages (more than 3 – 3.5 acres), as economies of scale are achieved with equipment.

- Above 3.5 acres, the tractor-driven roller-crimper was the cheapest to implement. When compared to the landscape fabric treatment, the cost of weeding in this roller-crimper treatment was made up for by the economy of scale achieved by the tractor’s higher working width and speed.

- Above 5 acres, the cost to implement the tilled treatment was practically equivalent to the tractor-based roller-crimped when considering variability across years.

- Mowing was the most expensive to implement overall. Compared to other treatments, mowing required additional time spent weeding compared to other treatments. Mowed plots are weedier because the cover crop mulch is chopped into small pieces that decompose quickly and let more light through to the soil surface (Figure 5).

Figure 3. Total cost of production by acreage for all treatments, scaled from 0.1 – 10 acres (A) to illustrate that method determines cost more than equipment above 3.5-5 acres, and scaled and 0.1 – 2.5 acres (B) to illustrate that equipment determines cost more than method at smaller acreages. n=2 site-years for tractor-based treatments; n=4 site-years for all others

Figure 4A. Manual crimper built for this project. (Left) Mary Carroll Dodd, Red Scout Farm, operates the manual crimper in the rye. (Right) Top: The crimper’s construction consists of 1.5” angle iron fastened to a 2×6, to which a rope is tied. Bottom: Cover crops recently crimped with the manual crimper.

Figure 4B. Roller-crimper for the walk-behind tractor. (Left)The roller-crimper is a lot to handle with a walk-behind tractor. (Right) Dylan Alexander, CFSA’s Lomax Farm Coordinator, operates the roller-crimper.

Figure 5. Plots at Red Scout Farm (four weeks after planting) show abundant weeds (crabgrass) growing through the mowed rye mulch (right), but the crimped rye mulch (left) is virtually weed-free.

4) Yield results, and therefore profitability results, were hard to compare across treatments because we experienced a crop failure at Lomax Farm in the first year (the only location where tractor treatments were implemented–see the write up for first-year results for more information, and where treatments were unreplicated in the second year). However, we completed two successful years at Red Scout Farm, where only a walk-behind tractor and manual treatments were implemented. When considering two years at Red Scout Farm and one year at Lomax Farm, we can draw very broad conclusions about yields and profitability (albeit not testable using statistics):

- Landscape fabric treatments tended to yield higher than other treatments (Figure 6).

- While we do not have the data to support the notion, it appears that–if studied longer–mowed treatments would likely yield less than crimped treatments due to higher weed pressure (unless more time were invested in weeding), and landscape fabric treatments would yield higher, due to fewer weeds and better nutrient supply to crops (faster breakdown of organic matter in soil and cover crops).

- At Red Scout Farm, yields in the landscape fabric treatment were 12-52% higher than in crimped and mowed treatments (two-year average). When considering this and the fact that the cost of production in the landscape fabric treatment was consistently lower than all other treatments (except tractor-based roller-crimped and tilled treatments above 3.5 – 5 acres; Figure 3), net profitability is consistently higher when using landscape fabric.

Figure 6. Marketable fruit yield (lbs/ac), breakeven yield (lbs/ac valued at $1/lb), and per-plant yield (lbs/plant; right axis) across treatments at both locations. Data from two locations are presented separately due to large yield differences between locations. Error bars are standard error of the mean (Red Scout Farm only); n=2 site-years.

5) Let’s build from the last bullet point but also acknowledge that yield data from Lomax Farm were unreplicated and highly variable. If we assumed that yield data from Red Scout Farm were at least somewhat representative of treatment effects (broadly categorized as crimped, mowed, and landscape fabric), then we could make some reasonable assumptions about profitability, albeit very cautiously.

- From this tentative data exploration, the landscape fabric treatment is more profitable than all other treatments, regardless of acreage (Figure 7).

- This is especially relevant at smaller acreages, where mechanized options are costlier to implement per acre (compared to other treatments) and therefore are the least profitable, possibly net negative (Figure 7B).

- However, just behind the landscape fabric treatment, the tractor-based roller-crimper is the second-most profitable treatment starting at 2 acres, once the upfront cost of the equipment is offset by economies of scale achieved with it (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. Net profit ($) by acreage for no-till treatments based on butternut squash valued at $1/lb (a conservative wholesale price), scaled from 0.1 – 10 acres (A) and 0.1 – 1 acres (B). Profit data were calculated using treatment-level yield data from Red Scout Farm (two-year average) in an attempt to provide reasonable yield estimates for tractor-based treatments at Lomax Farm, where data were unreplicated and highly variable. This is a tentative data exploration and should be interpreted cautiously. However, it provides insight into how profitability may differ among treatments at different acreages. Note: tilled treatment not included due to lack of replicated data.

6) Finally, tilled treatments performed comparably or better than most no-till treatments:

- Fewer labor hours

- Similar cost of production to tractor-based roller-crimped above 5 acres

- Similar yields to landscape fabric*

- Potentially equal or better profitability than landscape fabric*

*yield and profitability insights are anecdotal and require more data to confirm.

The fact that tilled treatments performed as well or better than no-till ones highlights the need for improvements in cover-crop based no-till production, especially when it comes to weed control. Thus, similar to first-year conclusions, we see two important but divergent ways to improve cover crop-based no-till production:

- When using a tractor or walk-behind tractor, the use of a high-residue cultivator has the potential to decrease investment in time spent weeding and improve crop yields. This is easy to accomplish for tractor-scaled production since the equipment already exists for a reasonable price. While such equipment does not exist for walk-behind tractors in a ready-to-buy form, it can be adapted and fabricated from existing cultivation equipment designed for walk-behind tractors.

- In roller-crimped and mowed no-till systems, weed control from high-residue cultivation is not as complete, and nutrient release from cover crops is slow compared to tillage-based systems and ones that use landscape fabric.

Because of this, we believe that roller-crimped and mowed systems will never perform as well as tilled ones (even with better weed control). We propose the development of new technology to mechanize the application and removal of landscape fabric, or similar material, to provide season-long weed suppression and improve nutrient supply to crops from more rapid decomposition of cover crop mulches.Technology such as this, if affordable–like many plastic mulch layers–could bring successful organic no-till vegetable production within reach for many more farmers, and have similar yield and economic benefits that plastic mulch had several decades ago when it was introduced, as well as significant benefits to soil health and on-farm conservation.

Questions? Want More?

- Read our first-year results: How Do Organic No-Till Methods Compare?, which includes a link to the full first-year report on Southern Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE).

- Bit by the research bug? Check out CFSA’s Organic Research section.

- Have questions? Want to participate in future no-till research? Email the article author, Mark Dempsey, at mark@carolinafarmstewards.org.

Support for this project was provided by Southern Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) grant OS 19-129 for the 2020 growing season and by Organic Valley’s Farmers Advocating for Organics (FAFO) for the 2021 growing season.