By Frank Hyman, Author of Hentopia: Create Hassle-Free Habitat for Happy Chickens | Thursday, Oct. 18, 2018 –

Water, water everywhere, but not a drop in the hen pen that’s fit to drink because it’s often mucked up with dirt, debris, or chicken poop. Yuck! Theoretically, keeping chickens can be a lot of fun. It can also be rich in drudgery. I’ve found that providing clean water is one of the lowest maintenance parts of your chicken adventure.

My wife, Chris, was the one who wanted chickens. I wanted the least possible hassle. When it came to watering, I searched the web, plowed through books on coops, and attended local Coop Loops. The result? I found two practices that now make up our hassle-free watering system.

The chickens have never fouled the water and we’ve only had to hand-fill the waterer three times in two years.

The first one was gleaned from a tour in Raleigh, NC. I saw how one hen-keeper, retired NC State professor and permaculturist, Will Hooker, had harvested rainwater for his hens. The second was discovered online; I found a couple that uses watering nipples – similar to a gerbil’s waterer – screwed into the bottom of five-gallon buckets. No saucer of water for birds to tip over or muck up. I combined these practices for our hen habitat and you know what? The chickens have never fouled the water and we’ve only had to hand-fill the waterer three times in two years. That’s about as hassle-free as you can get!

Here’s how we did it.

First, Harvest the Water

Will Hooker, who I mentioned above, is a popular permaculture teacher and one of my design professors at NC State University. He collects thousands of gallons of rain from the roof of his house into large cisterns to water his garden. In the same fashion for his chickens, he harvests the rainfall from the roof of their chicken coop using a store-bought rain gutter screwed to the eave of the coop’s roof. The water then goes through a downspout into a 35-gallon plastic cistern with a tap. Hooker and his family use this rainwater to refill their chickens’ waterers.

Will Hooker’s set up that inspired us so many years ago

My wife and I saw this set-up long before we got serious about chickens. I knew, even then, that we would steal – I mean borrow – this idea of harvesting rainwater for our hens. Chickens need to drink about a pint of water a day depending on how hot it is. The five-gallon bucket we use holds enough water, up to 40 pints, to last our three hens about two weeks without refilling (think “worry-free vacation”).

Chickens need to drink about a pint of water a day depending on how hot it is.

In the Eastern United States, we can reasonably count on a decent rain every 10 days or so, unless a drought has set in, which automatically top-up the waterer. As I mentioned above, we’ve only had to re-fill it by hand a few times in several years. In drier climates obviously, the birds will be thirstier and the rains will come less frequently, so choose a bigger container, multiple containers, or be ready to top it off yourself more often.

Some people wonder if this water is safe to drink, which is a question that begs consideration of one’s roofing material. Rainwater collected from asphalt shingles can have hydrocarbons (since asphalt is the gunky stuff at the bottom of a barrel of oil after they’ve refined the lighter kerosene, gasoline, and other products from it). Plenty of people provide their hens with rainwater from these asphalt-shingled roofs and the chickens do fine. However, cedar roofs and metal roofs will give hens cleaner water. For the sake of greater coop character, and cleaner water, we installed a metal roof. You may find cheap, metal roofing at your local metal scrapyard.

Our Hentopia, with a red, metal pagoda roof

In order to get the water from the roof to your waterer requires two things: a gutter and a downspout. While visiting the local metal scrap yard years ago, I picked up some copper gutters and downspouts cheaply. (This was before the price of metals jumped.) I stored them behind the garage, with no purpose for a long time, until Chris’ desire for hens gave them some value on our urban homestead.

Since two different metals touching often causes corrosion, rather than using steel screws or nails, I used thin copper wire to suspend the copper gutters from the wooden parts of the coop roof and the chicken run. If you use store-bought or recycle standard aluminum gutters and downspouts, you can safely use the screws or nails that come with them. The main trick with gutters is to use a level to make sure that the gutter isn’t level: it has to run slightly downhill – toward your cistern – so the water will flow into the downspout and not sit stagnant in the gutter, providing habitat for mosquitoes.

Scavenged copper gutter and downspout supply the water bucket

What about algae?

Algae needs light to grow. If the water container is translucent – you can see the level of the water through the walls – or it lacks a top, you will have algae growing in the water.

Since algae isn’t harmful to chickens, we don’t worry about it. There is a considerable amount of algae growing in the ponds that wild animals drink from. And we have yet to see algae clog the watering nipples. On the occasion that the water is low enough to justify topping off by hand, we remove the bucket and rinse it out to clean out any algae or debris that’s fallen in.

Avoid algae growth by using a dark container, painting the outside of a translucent container, and/or keeping a cap on it. Cutting a hole in the cap just large enough for the downspout to go through lets water in and keeps light out.

Second, Water the Hens

I wanted to avoid using any chicken waterers that had saucers. Chickens often get them dirty and then the waterers would need regular cleaning.

Surfing on the web I found Avian Aqua Miser by Anna Hess, author of The Weekend Homesteader, and her husband Mark Hamilton. Mark also wanted to reduce his workload. He used watering nipples screwed into the bottom of plastic buckets and bottles as a way to water their chickens–similar to the waterer for a gerbil. Disturb the tip and water comes out; leave it alone and the water stays contained. The water is clean, there’s no saucer to get dirty, therefore no need for daily cleaning! I immediately decided to steal, again I mean borrow, that idea too.

If you’re not handy, Mark and Anna can sell you a complete waterer. If you are handy, they can sell you a DIY kit or you can buy the watering nipples from most local ag supply houses. You’ll need an 11/32 drill bit to make the hole in the bottom of your bucket. That will be just the right diameter for the threads of the watering nipple to bite into the plastic and create a watertight seal. It’s worth spending the extra money for the nipples that have a rubber gasket, to ensure they won’t leak.

You’ll need an 11/32 drill bit to pre-drill holes for the watering nipples

If you’re making your waterer in the winter, let the buckets get to room temperature indoors before drilling. The drilling will work at any temperature, but if the buckets are cold, the plastic won’t be flexible enough for the threads of the watering nipples to bite; they’ll just go around in circles. One watering nipple is enough for about three birds and three nipples are the most you’d want to put on a five-gallon bucket.

Some people attach watering nipples to PVC pipe (fed by a waterer) instead of the bottom of a bucket, which may work for your pen. However, the curved sides of the PVC pipe may make the watering nipples more likely to leak than the flat bottom of a bucket.

I’ve suspended our waterer from a couple of scraps of wood attached to a brick wall with masonry screws. Farm Tek, a catalog company, carries a collapsible bucket holder that I may switch to. There’s also a less expensive holder that doesn’t collapse.

Mount the bucket at or above shoulder height for the chickens so they can reach it.

Using Farmtek’s folding bucket holder and an opaque bucket from Lowes

You Can Bring A Chicken to Water, but…

The chickens won’t instinctively know how to use the watering nipples to get water.

The chickens won’t instinctively know how to use the watering nipples to get water. Your best bet is to remove other water sources, then catch and hold the dominant chicken so its beak is beneath the bucket. Lightly bump its beak against a watering nipple until water dribbles out and onto their beak. At first, they’ll squawk, wondering why you’re tormenting them so. But you’ll see the light dawn on them when the bird realizes where its water will come from. She will start drinking. If you’re lucky, the other chickens will see the dominant hen drinking from the watering nipples and get the idea too. But don’t count on it. You’ll get quicker results giving them their own intro to the watering nipple. But, again, that’s still so much easier than cleaning up dirty saucers of water.

Rosie and Dahlia catching up on scuttlebutt at the water cooler

With the time you save you can pull up a chair and watch the hen show while sipping your favorite beverage—from a nice clean glass.

Frank will present “Hentopia Coops & Habitat for Chicken Keepers” at this year’s Sustainable Agriculture Conference, on Saturday, November 10th, during Workshop Session D, from 3:15 – 4:30 p.m. We hope to see you there!

Frank Hyman is the author of Hentopia. A designer, builder, gardener, and freelance writer, Hyman leads workshops on designing and building chicken coops and hen habitats. He has written for Organic Gardening, Modern Farmer, Fine Gardening, Hobby Farms, and the New York Times. He lives and maintains his own flock’s hentopia in Durham, North Carolina.

Frank Hyman is the author of Hentopia. A designer, builder, gardener, and freelance writer, Hyman leads workshops on designing and building chicken coops and hen habitats. He has written for Organic Gardening, Modern Farmer, Fine Gardening, Hobby Farms, and the New York Times. He lives and maintains his own flock’s hentopia in Durham, North Carolina.

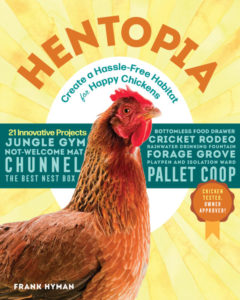

Hentopia: Create Hassle-Free Habitat for Happy Chickens: 21 Projects comes out in December 2018

All images by Frank Hyman.